In 2009, Paul Graham authored "Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule," outlining two distinct working styles: makers and managers. Graham discussed how makers struggle with focus and morale disruptions, primarily caused by meetings. He emphasized the conflicts that arise when leaders, often managers, fail to grasp the impact of imposing their work style on makers. Graham aimed to promote understanding and accommodation of these differing work styles to reduce conflicts and foster team success.

Today, the workplace is undergoing a rapid and profound transformation, embracing remote and hybrid work models driven by technology and aligned with managers' schedules. This shift underscores the importance of preserving makers' schedules. As we approach the future of work, it's crucial to revisit Paul Graham's ideas and implement practices that support the flourishing of both work styles.

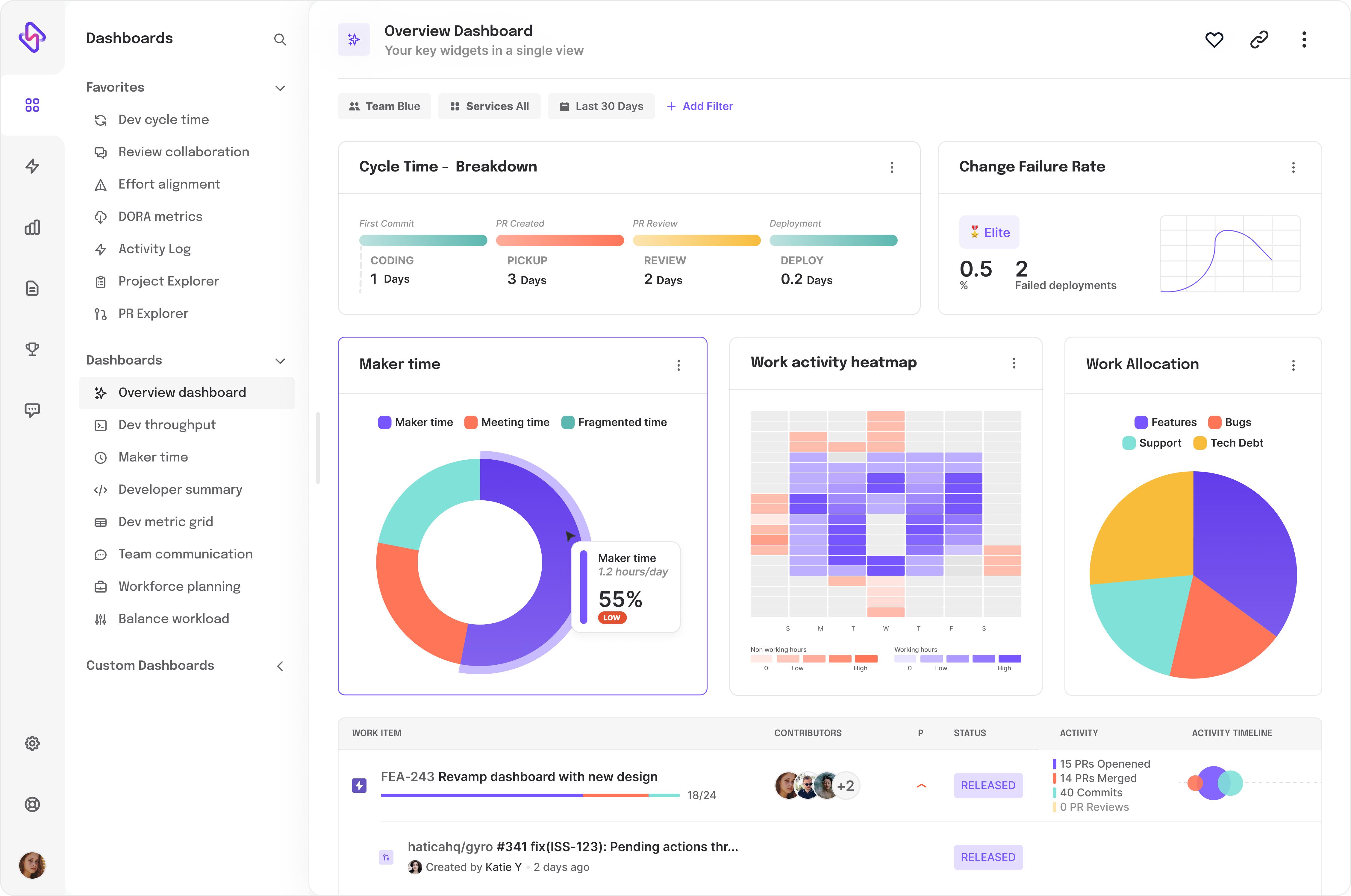

In this blog, we examine the differences between the maker's schedule and the manager's schedule, and how to use metrics and work analytics to navigate the changing nature of the workplace.

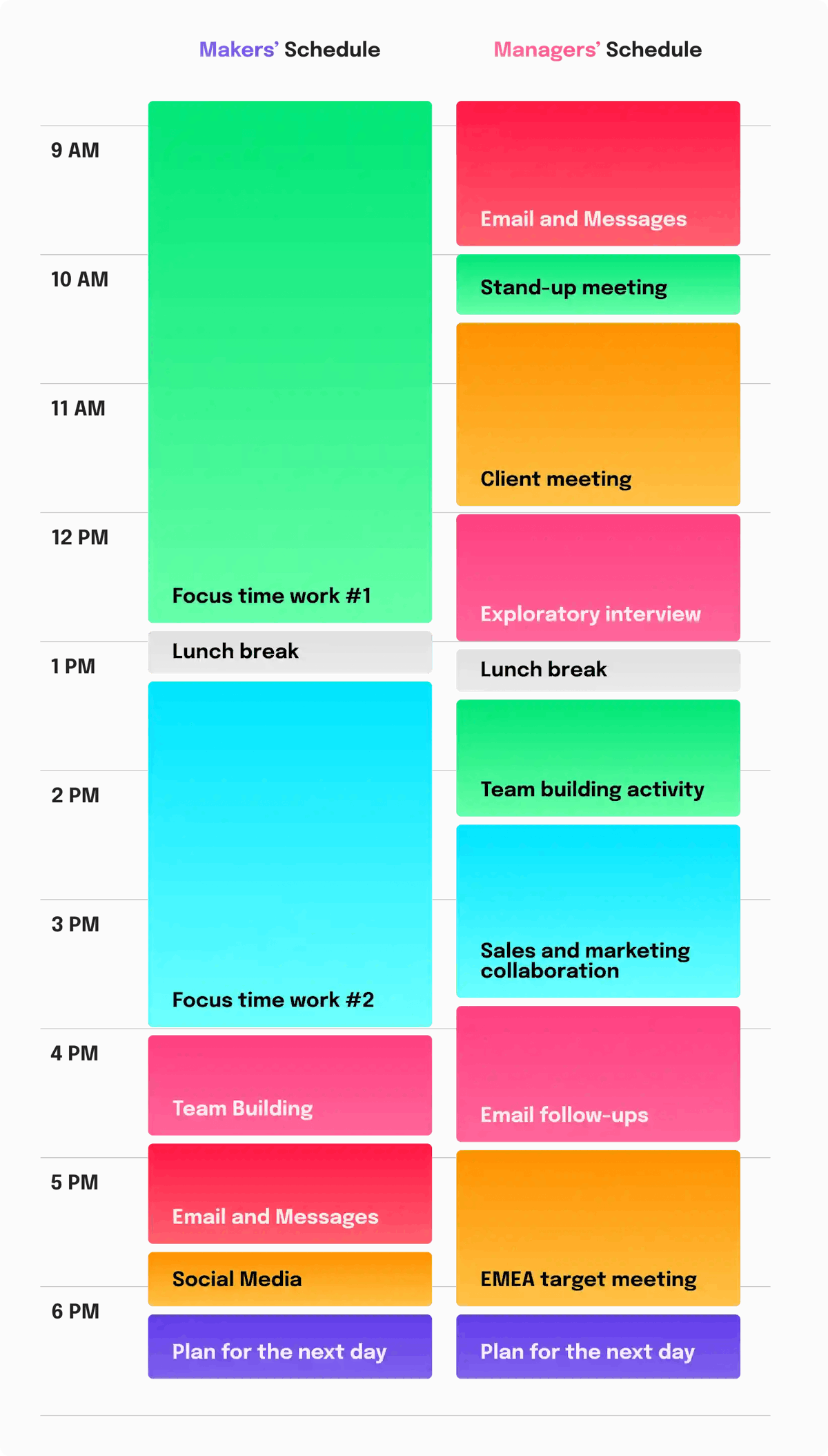

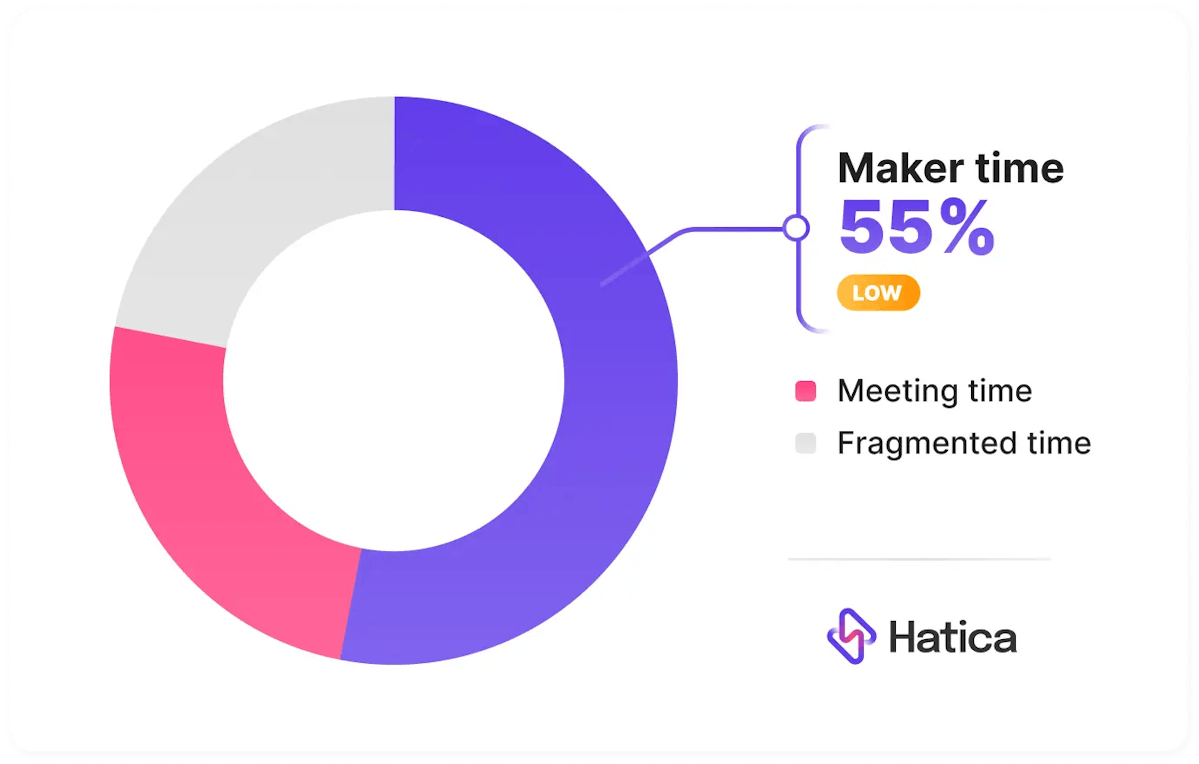

The Maker’s Schedule

The maker’s schedule is designed to allow long, uninterrupted slots of focus time spent working on cognitively demanding tasks. This schedule is fundamental to facilitating what Cal Newport calls “deep work”, where an individual is able to dedicate many uninterrupted hours to a core task, essentially getting into a state of flow and performing at peak productivity. In this schedule, any interruption during focus time disturbs the individual’s state of flow.

Let us consider an example of a senior developer Jane here,

Picture a day in the life of Jane, a quintessential maker/senior developer at a remote-first and distributed tech company. Her workday starts at 9 AM, she goes through a team check-in, answers some emails, and then goes into a DND mode between 10 AM and 2 PM when she prefers to write code. In this uninterrupted stretch of time, Jane enjoys the uninterrupted quiet, the almost perfect mirroring of the still focus of her mind reflected in her environment and therefore in her work. At this time, she’s in a state of flow – her creativity is abundant, her focus is sharp, her work is impeccable, and when she closes work, she feels completely satisfied.

The Manager’s Schedule

In contrast, the manager’s schedule is structured to accommodate several meetings. Managers and bosses often view their days as hourly time slots that can be used to run meetings, respond to communication, plan strategies collaborate with others, etc. Managers, for the most part, do not spend long hours in siloed focus, instead, their productivity is maximized and measured by how much they are able to organize and manage the people reporting to them, often involving voluminous collaborative outreach.

Let us consider an example of Kat, who is Jane’s manager,

Kat’s workday is a picture of an individual on the manager’s schedule. Kat is Jane’s manager, managing 12 software engineers across three distributed offices. Most of her day is segmented into hour-long meetings, scheduled with scrum calls, team meetings, virtual cross-collaboration meetings with other teams, and executive meetings. Even if she manages to find a window of time for focus work, the consciousness of upcoming engagements preoccupies her the whole day.